Danny O'Brien

Technology journalist and writer known for his work on life hacks and productivity.

Technology journalist and writer known for his work on life hacks and productivity.

instructions.md, is crucial. These files should contain:

VS Code automatically detects the Python interpreter for a project and activates the corresponding virtual environment in the shell, unless the project lacks one. Although I saw that even when the virtual environment was deleted and I deactivated the env, when I reopened the Project, the Virtual Environment was already activated.

To resolve this, I used Command + Shift + P, selected Python: Clear Workspace Interpreter Settings, and then chose Python: Clear Cache and Reload Window.

Watched Simon Willison: The Future of Open Source and AI | Around the Prompt #10

To start the server for the first time:

docker run -d -v ollama:/root/.ollama -p 11434:11434 --name ollama ollama/ollama

To stop and start

docker stop ollama

docker start ollama

To interact with it:

docker exec -it ollama ollama pull gemma2

docker exec -it ollama ollama run gemma2

FYI: gemma2 needs more than 8GB of RAM to run.

→ docker exec -it ollama ollama run gemma2

Error: model requires more system memory (9.1 GiB) than is available (8.4 GiB)

To move Ollama models to an external SSD when using Docker:

docker stop ollama

mkdir /Volumes/YourSSD/ollama-models

docker run -d \

-v /Volumes/YourSSD/ollama-models:/root/.ollama \

-p 11434:11434 \

--name ollama \

ollama/ollama

If you already have models and want to move them:

docker cp ollama:/root/.ollama/. /Volumes/YourSSD/ollama-models

docker volume rm ollama

iA Writer has an Authorship feature which can mark the text source. I’m trying to find a plugin for Obsidian that uses these annotations.

Creating POCs can give us more insights since we’re touching the real thing, even if it’s just a spec file where we’re trying out a new library or a concept.

Try to keep the POC in one spec file so everything is in one place. This works fine for backend features. But how would one handle UI changes?

Sometimes creating a new playground (in the form of a separate project) can also be a tool to try out something. Then we can use the experience acquired from it to implement the idea in the main project.

Experience can only be developed via getting our hands dirty, so it’s more important to try out new things than reading about them.

We should aim for trying out something, not reading about it.

One form of gaining experience can be creating POCs 2.20.1

This note is talking about the same idea as I had earlier in 2.20.2. Both notes emphasize that 2.20.2 we need to engage directly with subjects to truly understand them.

Annotations from A high-velocity style of software development

I want to have a chat with the computer in its own language right from the start.

I like the idea of coding is a way of having chat with the computer. POCs are touching the real thing, even if it’s a spec file where we’re trying out a new library or a concept. This article also talks about creating playgrounds (as separate projects) to try out new features before implementing them in the main project.

Ideally, I would have a project consisting of just a single file that I don’t have to leave for hours on end.

So this means we should keep a project in one file? This can be an Rspec file too. How would one handle UI features?

Nobody sees these ugly scraps but me. I can decouple and isolate parts of the project as a result, and work on them independently without the need to keep calling all the different modules all the time or fire-up all parts of the project on each code change.

To me having a spec file which contains experimental code seem better than having it inside the implementation files.

Flowing data through pipes allows the execution of functions to also take place without specifying the arguments. They are implicit, like one would flow data through a Linux pipe. There are no intermediate variables and assignments.

This seems interesting. I should ask about this from ChatGPT.

That gut feeling is only developed through experience, through trying things out, failing and trying again.

Experience can only be developed via getting our hands dirty, so it’s more important to try out new things than reading about them.

We should aim for trying out something, not read about it.

This is an example article written by Cursor after collecting notes from my Zettelkasten, creating a tree structure, and asking it to generate an article from those notes.

The Zettelkasten method provides a systematic framework for organizing and developing ideas. By utilizing the human mind’s strengths in recognizing patterns and making intuitive decisions, this method facilitates effective knowledge management. This article examines the goals, processes, and applications of the Zettelkasten system, drawing insights from various linked notes.

The Zettelkasten method focuses on externalizing thought processes to improve problem-solving and idea generation. This approach is similar to the GTD (Getting Things Done) methodology, which also emphasizes transferring mental tasks to external systems, allowing the mind to focus on more creative and intuitive work.

The Zettelkasten workflow aims to break down research, learning, and idea development into clear, manageable steps. This structured approach supports analytical and comparative reading and integrates these processes into daily routines, making complex tasks more accessible.

A key component of the Zettelkasten method is the collection and processing of notes. For example, during reading sessions, notes should be exported to an inbox immediately afterward to maintain the context and freshness of ideas. This practice ensures that notes remain useful for future idea development.

The Zettelkasten can be used to advance R&D projects by serving as a framework for managing information and connections. This method provides a historical view of learning progress and helps identify the next steps in the research process.

The Zettelkasten method aligns with the GTD’s Natural Planning Model by allowing ideas to develop organically. This approach avoids forced idea generation, instead fostering an environment where the mind can naturally connect and expand upon existing knowledge.

The Zettelkasten system is particularly effective in project management, especially within the GTD framework. It supports the development of Someday/Maybe lists and facilitates the organization of project-specific notes, which can be stored separately from the main note collection.

The Zettelkasten’s structured approach can be adapted for product development, where the steps of writing are translated into stages of product design and implementation. This includes transforming ideas into functional specifications and tracking their progress through development.

A fundamental principle of the Zettelkasten method is atomicity, which involves breaking down ideas into discrete, self-contained notes. This principle ensures that each note is independently understandable and can be recombined with others to form new insights and connections.

The Zettelkasten method offers a structured framework for managing knowledge and fostering creativity. By externalizing thought processes and leveraging the mind’s natural strengths, it provides a flexible approach to idea development and project management. Whether used for personal knowledge management or professional development, the Zettelkasten system is a valuable tool for enhancing cognitive processes and productivity.

We can’t learn to swim from the internet.

When we read about something, we don’t gain firsthand experience with it. Instead, we merely observe the author’s insights. The most effective way to learn about a subject is through active engagement with it. This allows us to witness its functioning (or failure) firsthand.

If we just read about something, we’re seeing the subject through the eye of the author.

Instead of simply reading about a subject, the best way to gain practical experience is to work on a project that allows you to apply your knowledge in some way. For instance, you could try using a programming framework for a personal project. LLMs can be also helpful in generating a working prototype, but it’s crucial to actually interact with the subject matter.

One form of gaining experience can be creating POCs 2.20.1.

When we have to explain an idea, it’s better to create something beforehand which will support our explanation.

Communicating visually enhances understanding, increases engagement, breaks down language barriers, and clarifies abstract concepts.

Proposed tools for creating visual explanations:

This is a list of frameworks and tools that I can use to figure out solutions to problems.

Claude AI now can control a computer, but it is in a really early phase. It can be useful for UI scripting or automated testing.

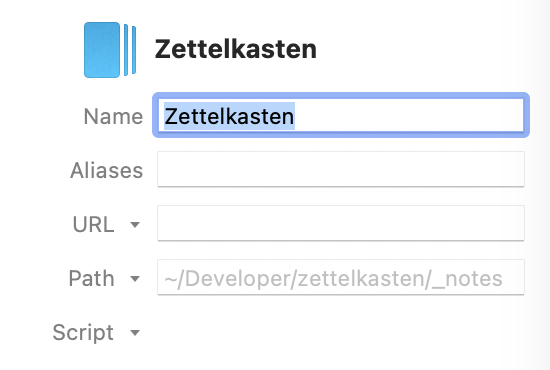

My problem is that my #Zettelkasten is a #Jekyll project and it doesn’t contain my notes in a nicely formatted folder name. If I want to index it, I have to rename it somehow.

It also seems to be possible to rename a group by

- only temporarily locking in Finder,

- renaming in DEVONthink,

- unlocking in Finder.

This solution works perfectly. We can just lock the folder in Finder, rename it in #DEVONthink, then unlock it. Now the folder name and the path will be different.

Notes about the programmer’s notebook concept:

Independent Writer, Speaker, and Broadcaster - Merlin Mann:

Merlin Mann is an independent writer, speaker, and broadcaster based in San Francisco.

{Git Bisect is a powerful debugging tool that helps you pinpoint the exact commit that introduced a bug in your project. This feature is a great example of how Git can be much more than just a version control system, offering valuable debugging capabilities as well!}

Git bisect is a tool to find a commit that causes a bug.

{First, you need to inform Git of a commit where the code is working correctly \(the "good" commit\) and another commit where the bug is present \(the "bad" commit\).}

First, we have to set a good commit and a bad commit. These will be the start and end points of a binary search.

{Git then selects a commit that lies halfway between the two points you provided and prompts you to confirm whether the bug is present in that commit.}

Git then finds a commit halfway through, and we have to test if the commit works.

{This iterative process continues as Git narrows down the range of commits until it pinpoints the exact commit that introduced the bug.}

Then, repeat the process, which means, after a while, it will find the buggy commit halfway somewhere.

So, it uses binary search to find the commit causing the bug.

{\$ git bisect start \$ git bisect bad \# Current version is "bad" \$ git bisect good \<good-commit-hash\> \# Commit that is known to be "good" \# Git then checks out a commit for you to test and you mark it as "good" or "bad" \$ git bisect good \# or git bisect bad, depending on your conclusion \# Repeat until Git identifies the problematic commit \$ git bisect reset \# to end the bisect session}

Here’s how we can start a git bisect session.

{allows Git to remember how you've resolved a merge conflict so that it can automatically resolve it the same way if it encounters the same conflict again.}

Git Rerere is a way to tell Git to remember the merge conflict I already solved and reuse it again.

{This is particularly useful when working with long-lived topic branches, as you may encounter the same conflicts repeatedly.}

There are long-living branches that always need to resolve the same conflict, so this can help in those cases.

{git config --global rerere.enabled true}

How to enable Rerere.

{Once enabled, Git will automatically record how you resolve conflicts and reuse these resolutions in future conflicts.}

I wonder if this will cause problems because I feel it makes me trust blindly in Git for conflict resolution.

“Finding information on the front end” means using the project view in #OmniFocus to fetch our project support data. Assets are linked to actions and projects, so instead of browsing the file system using Finder, we start from the project and jump to related assets.

Starting from the project view allows us to use the OmniFocus quick-open to find projects and navigate to related information instead of general categories where we have to drill down multiple levels to find folders or files.

We should have a published section in the project plan. Or we can link to published assets using Hookmark. This is how we can prove that the project is actually producing output.

The published abstraction can be a physical thing that we made:

This note is the possible continuation of 2.8.4 Szabályok a digitális végtermékek előállítására.

Starting out in 2001 as both a writing tutor and high school substitute teacher, for the past twenty years Bob has been teaching and mentoring everywhere from public schools to punk warehouses to living rooms to online Zoom rooms and colleges. These days, he teaches courses on zettelkasten, PKM, social media, and spirituality. He is a former Building a Second Brain mentor, was the managing editor of _Parabola_ magazine between 2005–2010, has been blogging since 2003, and publishing zines on and off since the early 90s. He is the author of five books:

- A System for Writing: How and Unconventional Approach to Note-Making Can Help You Capture Ideas, Think Wildly, and Write Constantly

- Sitting with Spirits: Exploring the Unseen World In the Margins of Christianity

- The House of I Am Mirrors: And Other Poems

- Acupressure For Beginners

- The Power of Stretching

You can stay up to date on his comings and goings by finding him online or by signing up for his weekly email “The High Pony: ‘Really Good’ Insights from a Modest Perch.” For everything else » bobdoto.computer

It doesn’t matter how a project is organized; #Hookmark should contain all the related assets and links to the project. The organization of these assets doesn’t matter: we should dump everything in one folder per project and not care how we will use that information in the front end 2.8.2.4.4.

So, a file system just sits in the background, supporting our more important project-related interface, which we can use to interact with the information.

{Folders are like servers. They're the places where all your information is stored. Files, working docs, notes, PDFs, resources, images, every digital thing you've collected is stored somewhere, be it in a vault or on a hard drive. In folders, this information is typically stacked alphabetically or in numerical order. The only real way to organize the contents of a folder according to what best suits you is to rename, number, or https://writing.bobdoto.computer/how-i-use-clogs-to-organize-my-writing-files/ Page 3 of 7}

Folders are there to organize information. I like this idea that the file system is a backend of my projects.

2.8.2.4.5 The file system is a backend for our projects

{If folders are servers, then CLOGs are user interfaces. A CLOG is the means by which I engage with my writing files so I don't have to engage with what's stored in my folders. Kind of like email.}

The CLOG is like an OmniFocus project. Linking resources to a project from folders.

I wonder if I need separate ideation folders. Would be just one TaskPaper document enough (Interstitial Journal).

What does he mean by kind of like email?

{Whenever you open Gmail, you're engaging with Google's UI. This UI allows you to curate what you'd like to see. When you're in Gmail, you're engaging with a representation of the information stored on the server. You're engaging with whatever you've allowed to pass through your pre-defined filters. When you delete an email, it disappears from your UI, but not necessarily from the server. CLOGs function in the same way.}

He explains email here.

So a folder is a backend, the project is the frontend of our system.

2.8.2.4.4 The project view is the frontend of our file system

{Underneath "PUBLISHED" I list all the places I published my piece and how it did on each platform.}

Having a published section for plans is actually helpful to see outputs of a project. So technically this should managed in TaskPaper. I don’t think I need the ideation database like I think. It should be one folder called Project Support, and that’s it. Maybe organize it by area, but otherwise the folder of a project is just a backend. How I use that information in my Interstitial Journal is what’s interesting.

I want to have a way to click from OmniFocus and filter everything related to a project in TaskPaper.

I have to use the OmniFocus ID.

2024-10-05_21-08 The published section for plans is helpful to see the outputs of a project

I found this workflow about how we can use an integration branch as a base for stacked branches.

Stacked branches with vanilla Git

Instead start the work by creating a feature-integration branch, which will contain all the changes you are working on together. Later, when you better understand the specific changes you are making, you can re-order the commits with git rebase -i to group commits together that you want to slice off as their own reviewable and mergeable branches.

We don’t know the hierarchy first of our work, so we can create an integration branch to mess around with ideas. The good thing is that this doesn’t need to be pushed. I can start working on the branch without too much structure and then organize my work later.

Naming these would be something like this: TICKET-ID/integration

This would be the source branch for the stacked branches so that Tower will show it as the first item in the branch tree in the sidebar.

Just like in typical programming, the commits are in no particular order. As so frequently happens, you only wrap your head around the overall change you want to make after you’ve touched a bunch of different pieces.

What does he mean by “commits are in no particular order”? Maybe I should ask ChatGPT… Here’s what it generated about this:

In a typical programming session, you might start working on one thing, then realize another part of the system needs to be changed, and by the time you’re done, the commits reflect this non-linear process. Only afterward do you gain a clearer understanding of the full scope of the changes you’ve made.

This mirrors the messy, real-world workflow where things evolve organically as you work, rather than being neatly planned out in advance.

This essentially means that we organize our commits after we create a mess. It could be avoided, though, with frequent committing and then squashing related ones later. This would force a commit review workflow on me, which can be helpful in Finding a session wrap-up process so I can wrap up my work more efficiently.

Then we have to somehow create the branches to point at the associated commits. Remember the rule though: never switch off your integration branch. So how are we going to create these branches?

We branch off from commits. Then, these branches are pushed and sent for code review. It is still important that a PR has the proper base, so we have to maintain some form of connection between them.

Or, it can be solved by pushing the integration branch too, and setting that as a base, but then we lose the nice local, private sandbox.

The beauty of this method is that you are still on the

feature-integrationbranch, ready to keep adding new work, whilefeature-acan go up for review.

In theory, this sounds good, but what about keeping stuff current?

I have to review these use cases first in Tower. I don’t care about the command line git for now.

Follow-up on 2024-08-14_23-33

I’m not sure if this is a good idea, but maybe I should hide the front page of my Zettelkasten? It would give me a way to discover random ideas.

On the other hand, I’m trying to make it more journal-like, so this idea would not help with that.

I’m introducing a new “Thought” tag, which will be used as entry points for the current threads I’m thinking about and developing.

The idea is to have an initial post tagged with “Thought” and follow-up notes are linked to that as a new reply. Over time, I’ll end up with a conclusion that can be developed into one or more permanent notes (2.6.9.5.1 and 2.6.11).

This is a remixed version of the #Folgezettel and 2.6.4 A strukturált jegyzetek a Zettelkasten belépőpontjai.

Follow-up on 2024-09-06_23-25

I want to find more ideas about using blogs as an external mind. Digital gardening is one way of doing this. 2.6.10

But I’m more interested in the commonplace book, where ideas are just thrown into a journal and, over time, developed into more refined ideas. I don’t care about nurturing the same post over the years.

My problem with that idea 2.6.10 is that I don’t know what the end result will look like. Instead of working on something for a long time, we should focus on outputting more posts and refining each new one better than the previous one.

This method was first mentioned in 2024-08-18_08-52 Writing Inbox in iA Writer.

These are my highlights from reading The Memex Method—Pluralistic: Daily links from Cory Doctorow.

The blog as an annotated browser-history

Is blogging like adding annotations to browser history? If you mainly blog about things you found online, sure…

Every day, I load my giant folder of tabs; zip through my giant collection of RSS feeds; and answer my social telephones – primarily emails and Twitter mentions – and I open each promising fragment in its own tab to read and think about.

If the fragment seems significant, I’ll blog it: I’ll set out the context for why I think this seems important and then describe what it adds to the picture.

So, his primary source is his web browsing. That’s fine.

My primary blogging sources also include my ideas. Maybe that’s why having a Zettelkasten is important at the end. Perhaps I should also keep a tab open for my ideas? I love the idea of fragments being opened in tabs. This is a nice metaphor since macOS tabs exist in the UI everywhere, so they provide a simple UI for fragments of information in apps that are made for browsing and managing information. See more about this in this thread, also related to this note 2025-10-07_00-12.

In the (my) blogging method, the writer blogs about everything that seems interesting, until a subject gels out of all of those disparate, short pieces.

So, blogging on its own can be a Zettelkasten-like way of emerging ideas as we develop them. Why do I need my Zettelkasten, then? Maybe my blog is my Zettelkasten. I think a Zettelkasten can help thread ideas together in an outline format, forcing ideas to emerge.

Blogging isn’t just a way to organize your research – it’s a way to do research for a book or essay or story or speech you don’t even know you want to write yet. It’s a way to discover what your future books and essays and stories and speeches will be about.

Blogging is a way of discovery, so blogging about something should be like date-ordered public thinking. Tags are subjects of interest. Maybe I should have more specific tags, like “Mac app renaissance.”

To conclude, my Zettelkasten is one of the backbones of my blog, along with journaling and browsing the web.

Follow-up on 2024-09-01_12-48

Looks like having the comma after the wikilink in follow-up notes will break the backlinks feature (relevant code).

For now, I’m going to use the following format:

Follow-up on wikilink

Follow-up on 2024-08-14_23-33

I forgot that I have a “Follow-up” button on my Zettelkasten website. This can be used for quickly writing a follow-up note about something I already started. Basically yet another way to create threads.

Then, I could save these threads by opening them on the website one-by-one and saving the stacked note URL.

Inbox workflow from Ploum:

I simply have an “inbox” folder where there are drafts in gemtext format. They could linger there for months or years. Sometimes, they are published one hour after starting them. There’s no rule.

I’ve been greatly influenced by Cory Doctorow and his memex method. In my inbox, I keep a “today.gmi” file in which I write small reflections and links to interesting articles. When the file is bigger than 1000 words, I try to give it a direction, I reorder the nuggets and publish it without thinking too much about it.

As a consequence, my blog is a mix of focused posts that took a long time to write, focused posts that were written in a whim and posts containing random thoughts and links. I let you try to guess in which category is a given post.

I like the ideas of this post. Having an inbox where my posts are drafted, then publish them directly. I should have a better system for using iA Writer in my everyday blogging, not just longer posts and the Zettelkasten-type notes.

I basically have a Bike outline named “Decoding”, which is used as daily notes and I can publish things directly from there. iA Writer is more for post drafts, or general ideas. I should maybe use it to draft stuff there. If something emerges, then maybe create a project for it in my Writings folder.

So this is the order of my idea flow:

I should just have one place, which is the #Drafting tag to use it as a writing inbox.

I really like how Andy Matuschak 2024-08-19_16-24-andy-matuschak uses the writing inbox concept. It is a list of ideas which should be worked on, then formed into something final.

I should have some form of flow with any material which is enters my life somehow, I work on it, shape it, then I have a final artifact 2.8.4 which can be used as a product that I’m sharing with someone (or me).

So when I’m working on something, I should ask that how this will be finalized?

Actually I should start my #Zettelkasten notes in #Drafts. When I have multiple ideas, it is easier to capture them in that app.

I can also pre-link these notes together in Drafts in the same as I can in iA Writer, so when I export them, the links should still work.

I’m thinking about giving up the general idea of the #Zettelkasten. I don’t have time to create permanent notes (or whatever we call them) and then link them together if I don’t use any of these notes in a writing project. And I don’t have any writing projects.

Instead, I want to focus more on using my #Zettelkasten as a journal-like medium where I can think freely in public and don’t have restrictions on how I format notes or link them.

This change means I would have more random thoughts like this, and if something is a returning thought, then maybe I’ll convert it into a more refined idea that can be stored in my outline.

On the other hand, if I read about an interesting topic, I would still use this page to store classic Zettelkasten notes (2.6.11).

Managing folgezettels means that I should have a general idea about why I’m collecting notes about a topic. Since a #Folgezettel is a thread, it should have some form of outcome. I can grab them as-is and finalize them into a blogpost or a project, or some form of plan.

When I see a #Folgezettel emerging, I could pick a bunch of notes and paste their content into #Gibberish. This way, I can create the first draft using a chat-like UI and get a feel for the final post.

Source: Making my file archive portable in a different way – Decoding

I concluded that each of these tools has its place.

I have a bunch of apps where I can manage information, and I should cut them back and figure out which one I’m using for what.

Here’s an initial list of my current use case of them.

The systematic approach to processing information from these various sources is detailed in 2.6.15, which shows how different inputs feed into a coherent content pipeline.

Follow-up: 2024-02-21_00-19-conclusion-on-my-journaltype-apps